The Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, has announced plans for GPs to start assessing patients’ risk of dementia from the age of 40 onwards, it’s been announced. He’s also promised ‘major strides’ in the care and treatment of people with dementia with the aim of reducing the ‘fear and heartache’ of a diagnosis.*[i]

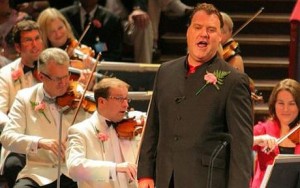

Reading the report is like listening to Bryn Terfel singing the barber’s song from Figaro while the orchestra is playing the Te Deum from Tosca. Indeed, Mr Hunt seems to be a master of dissonance. For the past few years he has been castigating GPs for not sending patients to Memory Clinics for early diagnosis, despite warnings from leading medical specialists that it could do more harm than good. But no, Mr Hunt said repeatedly, early diagnosis meant that patients would receive ‘tailored care and support.’ The phrase became a kind of theme song throughout 2014 and 2015.

The problem was – and still is, that there is hardly any ‘tailored care and support’. From what we glean from people at conferences, etc., it seems that there are a few pockets in the country, mainly semi-rural areas, where support is available, but not nationwide. A survey by the Royal College of GPs last November found that 70% of GPs surveys said there was no, or only inadequate care in their regions. Research by the Alzheimer’s Society found that many carers ‘find it impossible to access help and support. When they do, they have waiting times of more than a year.’[ii]

Something else Mr Hunt seems to overlook is that the rate of dementia has dropped considerably in the age group he proposes to target. In 2013, the Lancet published a study showing that the number of people with dementia in the UK was then 670,000, not the 800,000 that were usually cited.[iii] This downward rate has continued, as Professor Carol Brayne of the Cambridge Institute of Public Health reported last year.[iv] It was due to improvements in living standards and education; factors thought to protect against dementia. “Incidence and deaths from major cardiovascular diseases have decreased in high-income countries since the 1980s,” she said. “We are now potentially seeing the results of improvements in prevention and treatment of key cardiovascular risk factors, such as high blood pressure and cholesterol, reflected in the risk of developing dementia.”

In all this, there’s very little mention of the psychological effects of a risk assessment on the people who receive it. Dementia is still the most dreaded disease, and the effects of negative emotions on the body are well known. In the depth of his troubles Job said that ‘the thing which I greatly feared is come upon me, and that which I was afraid of is come unto me.’ Fear, anxiety and depression greatly increase the risk of dementia. A press report recently quoted a study that found that people who were afraid of dementia were more likely to develop it. ‘Above all else, guard your heart,’ says Proverbs 4:23, for it is the source of life’s consequences.’ (CJB)

A couple of months ago I drove two and a half hours to another part of the country for a seminar about the clinical trials of a new drug. After the talk, which explained about the trial and who could register (everybody and anybody) there were questions from the audience. One person asked what help and support there would be for people who took part in the trial but found the drug could not help them. There was none, was the answer. No counselling, no after care, nothing. A colleague who came with me recently met someone who had taken part: the medication had not helped her.

It makes me question the ethics of trials like this that have no care for participants afterwards, and more – the ethics of introducing to healthy people in the assessment process the notion that they may develop dementia. GPs don’t do it for any other disease, as far as I know.

Yet, as Professor Brayne noted, the most effective ways of preventing dementia are well known. They are the things that make for good cardiovascular health – exercise, a healthy diet, a reasonable weight and blood pressure. What isn’t so widely known but is possibly even more important is the need for sufficient sleep (the brain clears cellular waste during a certain sleep phase), and staying socially connected. And the biggest impact on health and longevity, according to Professor Durban of Oxford University, is staying socially connected. Loneliness increases the risk of dementia by 47% and depression by up to 50%.

[i] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/nhs/12184011/NHS-will-carry-out-dementia-checks-at-40.html

[ii] Daily Express, Thursday February 4, 2016

[iii] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-23326061?dm_i=OXC,3WNIS,IPCG34,E31NR,1

[iv] https://louisemorse.com/better-lifestyles-beat-back-dementia-epidemic-in-younger-age-groups/