Two decades of research into Alzheimer’s disease have failed to produce any effective therapies and the time has come to change direction, said the director of the new Dementia Research Institute being set up in University College London and over three other research centres.

Two decades of research into Alzheimer’s disease have failed to produce any effective therapies and the time has come to change direction, said the director of the new Dementia Research Institute being set up in University College London and over three other research centres.

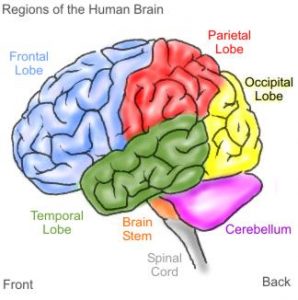

Last year the new centre’s director, Bart De Strooper, published a research paper challenging the ‘amyloid hypothesis’ that has been the main driver in dementia research since the 1980, in the belief that Alzheimer’s was caused by the build-up of protein deposits in the brain (amyloid B and Tau). In recent months, three clinical trials on drugs to remove the deposits have failed.

The focus on removing the deposits seems to have ignored some well documented anomalies, such the Religious Orders Study (ROS) and its companion study, the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP). Researchers found that the brains of a third of individuals studied had the protein deposits but no dementia. There was also the Nuns’ Study, where 700 retired teachers were followed for years as part of a health in ageing project. They agreed to donate their brains for examination after death. Researchers found that some with extensive deposits had exhibited no sign of dementia and some with only light deposits had developed deep dementia. The correlation was less than 22%. Another report stated, ‘abundant neuropathology in persons without dementia is observed as well, and the correlation between neuropathological lesions and cognition is modest, accounting only for about a quarter of the variance of cognition among older adults.’ [i]

Now Dr Strooper is directing researchers to examine the role of inflammation and the interaction with mycroglia, the brain’s immune cells. Microglia is already under the microscope.

A chapter in ‘Dementia: Pathways to Hope’ included a roundup of research approaches, including a study (University of Rochester Medical Center, New York) that described how microglia cells clean the brain of cellular waste during sleep. Researchers found that a single protein called EP2 stopped the action of the microglia cells, and blocking this protein with a drug reversed memory loss and other Alzheimer’s like features in mice.

A chapter in ‘Dementia: Pathways to Hope’ included a roundup of research approaches, including a study (University of Rochester Medical Center, New York) that described how microglia cells clean the brain of cellular waste during sleep. Researchers found that a single protein called EP2 stopped the action of the microglia cells, and blocking this protein with a drug reversed memory loss and other Alzheimer’s like features in mice.

The effect of negative emotions, such as feelings of loneliness, stress and depression, are also implicated in dementia. In his seminal work, ‘Dementia Reconsidered’, Professor Tom Kitwood hypothesised that negative feedback from a ‘malign social pathology’ (the culture a person is living in) creates a biochemical environment that affects neuronal health. ‘All events in human interaction – great and small – have their counterpart at a neurological level’, he said. ‘Derogatory treatment of an individual, based on stigma and ageism, has a profoundly negative effect that can lead to nerve tissue damage, whereas … relating that honours the individual has a positive response that ‘may correspond to a biochemical environment that is particularly conducive to nerve growth.’

[i] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4060425/