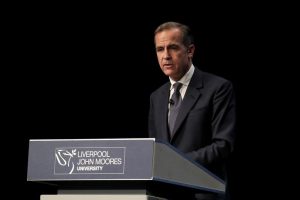

One of the most extraordinary speeches by a Governor of the Bank of England was given last evening. I’m amazed that it hasn’t been more widely reported, and that the BBC ignored it altogether.

We heard that Britain is experiencing its first “lost decade” of economic growth for 150 years, and that it was “incredible” that ‘real incomes had not risen in the past 10 years. He’s right. I know two brothers, one who’d worked in a factory on a machine 10 years ago, and now his brother is doing the self-same job. And the wage is exactly the same now as it was back then, to the penny.

There is a growing sense of “isolation and detachment” among people who felt left behind by globalisation, said Mr. Carney. He didn’t mention older people, but I did in my book, ‘Dementia: Pathways to Hope’, published earlier this year.[i] As well as depressing wages and devaluing skills, commercial globalisation has an even more devastating effect on older people by removing their main supports in old age – their families, who move away for work. I wrote:

‘Perhaps the most rapid change in human behaviour, and by far the most significant, is the phenomenon known as globalisation. It’s been happening gradually for hundreds of years but has been speeded up in the last 20 by the arrival of the internet. Our High Streets are disappearing as we purchase more and more online. Local producers have become specialists, and global corporations are taking over, and the biggest companies are no longer national firms but multinational corporations with subsidiaries in many countries. Some global corporations are more powerful than national governments, with turnovers surpassing countries’ GDP (gross domestic product).

‘The effects were foreseen, and warned about. In a paper published in the journal Ageing and Society,’ [ii] Gail Wilson, Department of Social Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, ‘wrote, ‘Free trade, economic restructuring, the globalisation of finance, and the surge in migration, have in most parts of the world tended to produce harmful consequences for older people. These developments have been overseen, and sometimes dictated by inter-governmental organisations (IGOs) such as the International Monetary Foundation (IMF), the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation (WTO), while other IGOs with less power have been limited to anti-ageist exhortation. ’

‘Dr Dhrubodhi Mukherjee was a consultant with the World Bank in their Urban Renewal Program in India. He is now Assistant Professor at the School of Social Work, at Southern Illinois University. Dr Mukherjee said, ‘Globalization has contributed to economic wellbeing for many developing nations, but it has reduced “family” into a non-viable economic institution for the elderly by promoting urbanized social values of individualism and atomic self-interest.’

Mr Carney noted that ‘Many people across the advanced world were “losing trust” in a system that did not “raise all boats”. Far from enjoying a “golden era”, globalisation … had become “associated with low wages, insecure employment, stateless corporations and striking inequalities”. Measures in the Autumn Statement, including higher investment spending, would “begin the process of rebalancing policies”, and putting “individuals back in control” by equipping workers with the skills needed to adapt to technological change were vital.

‘The tide must be turned back on stateless corporations” in order to maintain a sense of fairness. “Companies must be rooted and pay tax somewhere,” he said.[iii]

But we can do something about it right now. We can go to our High Streets and our corner stores and begin to buy locally. Many bookshops, including Christian bookshops, have been hit hard by globalisation. It’s so easy to buy from Amazon and the likes.

What about older people in the community? From our talks with Christians and churches we know that many are working hard to make sure they are not alone this Christmas. And that many have outreach programmes the whole year. And of course, we’re hugely privileged to support them in our housing and homes (se website, www.pilgrimsfriend.org.uk)

But perhaps it requires an even more fundamental shift in our thinking. A very timely book is the Bishop of Canterbury’s new book, ‘Dethroning Mammon.’ I found myself disagreeing with Justine Welby’s winsome vignette about Lazarus and his sisters, Mary and Martha – that perhaps Lazarus was living with his sisters and being cared for by them because he may have had learning difficulties. In the patriarchal society in the middle east in those days females lived with their male relatives, not the other way around. But the rest of the book is brilliant, and I recommend it, along with ‘Dementia: Pathways to Hope’, of course!

The Governor of the Bank of England has shone a light on the reality of globalisation. The Archbishop of Canterbury shows how we have fallen under the rule of Mammon, the false God. My book shows how to relate to older people, and how to honour them. But it’s down to us to actually do something about it. Each one of us is only a small stone, but if we each step into the water by supporting local enterprises, together we can become a dam.

[i] Published by Lion Monarch, available from retailers and also from our website www.pilgrimsfriend.org.uk

[ii] Ageing and Society, 22, pp 647-663. doi:10.1017/S0144686X02008747.

[iii] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/12/05/mark-carney-warns-first-lost-decade-150-years-brands-eurozone/